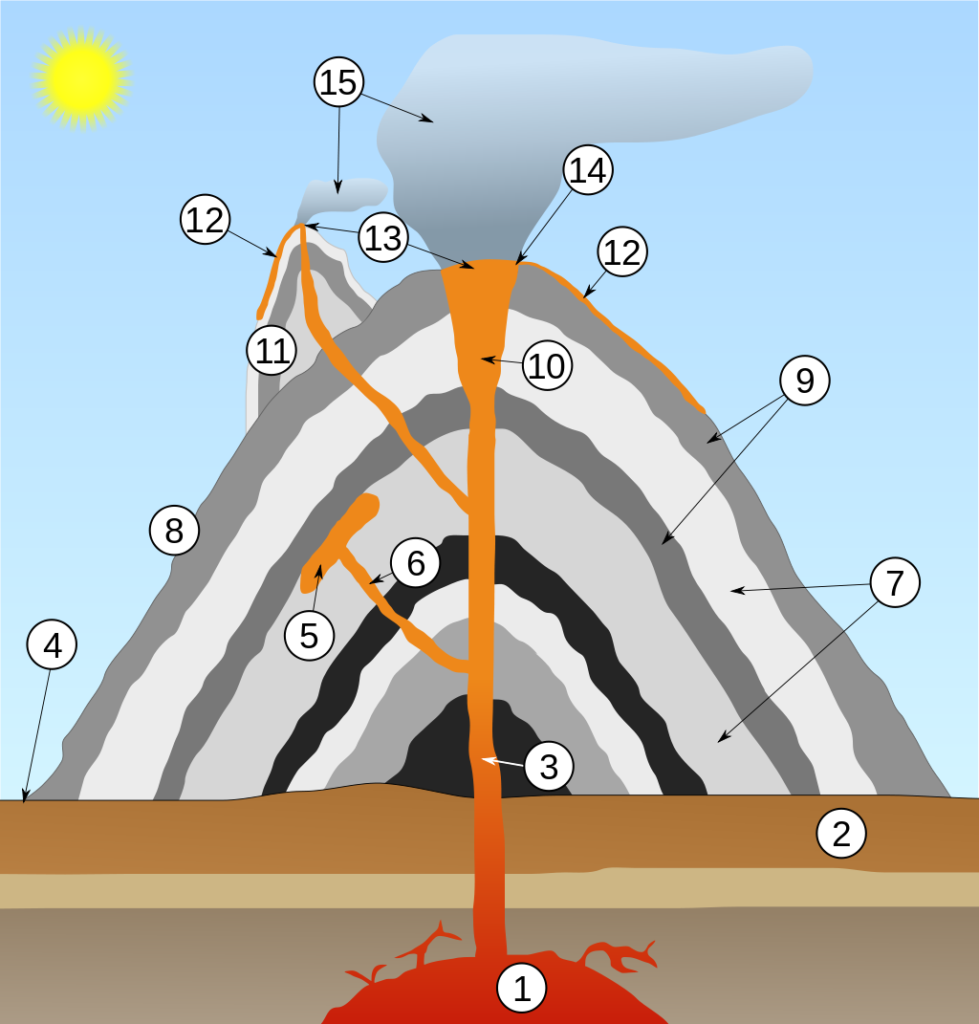

Do you know the different types and features of volcanoes? Volcanoes are vents in the Earth’s crust from which molten rock from below the crust erupts out onto the surface. When below the surface, this molten rock is called magma. When it is erupted or flows above the surface, it is called lava. Erupting volcanoes may release hot gases, fragments of rock or ash. Many factors affect these outcomes, primarily the various types and features of the volcano.

Formed at the boundaries of the Earth’s tectonic plates, volcanoes can be found on all continents. At present, there are 1,500 potentially active volcanoes around the globe. Most of these are situated in the Pacific Ring of Fire. This horseshoe-shaped zone stretches from New Zealand, through Southeast Asia, Japan, the West Coast of North America, and down to the southern tip of South America. However, these volcanoes are not geologically connected and function independently.

Volcanoes are forces of both great destruction and creation. Their eruptions can prove devastating to nearby life and infrastructure. Volcanoes are also responsible for crafting more than 80% of the surface of the Earth. Volcanoes create mountains, craters, and other landforms. Over time, volcanic rocks eroded into nutrient-rich, fertile soil that has benefitted many civilisations.

Types of Volcanoes

Volcanoes are by no means uniform in appearance and come in all shapes and sizes. Volcanoes can be cone-shaped with steep slopes, while others are wide, flat, and gently sloped. The structure is dependent on the characteristics of the magma that it extrudes.

Stratovolcanoes

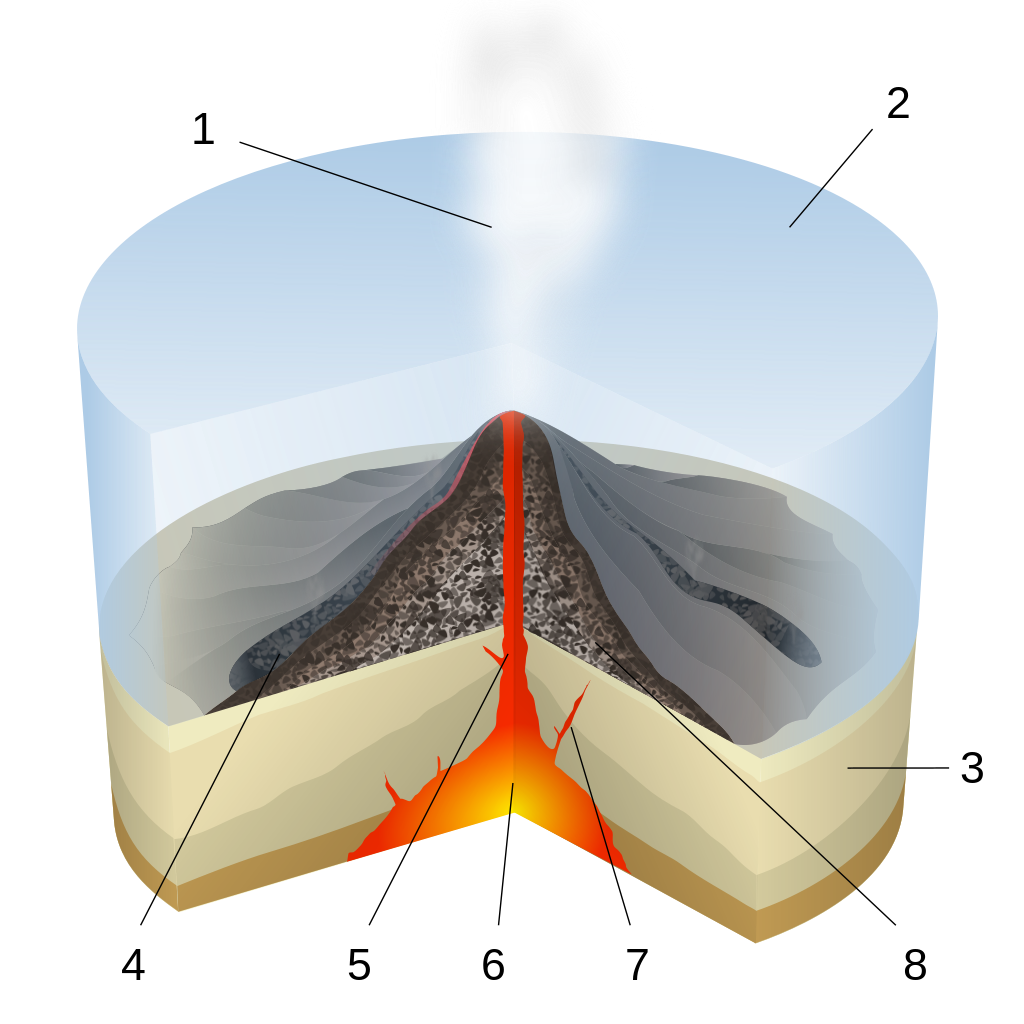

Stratovolcanoes are steep-sided, cone-shaped volcanoes formed by the eruption of sticky, viscous magma from below the Earth’s crust. Stratovolcanoes consist of layers and layers of solidified lava from previous eruptions. The viscous composition of the lava that these volcanoes extrude prevents it from running off and flowing easily. The lava accumulates near the vent, forming steep slopes that gradually become steeper towards the summit. For this reason, stratovolcanoes are sometimes referred to as composite volcanoes. The summit usually has a crater.

Stratovolcanoes mostly consist of andesite, a type of volcanic rock. However, they can also erupt a variety of rocks depending on their tectonic setting. Stratovolcanoes may also be composed of other volcanic rock types such as basalt and rhyolite.

Volcanoes that fall under this type can erupt thousands of times over millennia. These typically begin with explosions of hot ash and pyroclastic flows, then end in the emergence of viscous flows of lava down the steep slopes. The eruptions of stratovolcanoes are often explosive, posing significant threats to nearby life. Gas often builds up in the viscous magma, making stratovolcanoes more likely to produce violent, explosive eruptions.

Mount Fuji in Japan, Mount Mayon in the Philippines, and Mount Etna in Italy are examples of stratovolcanoes.

Mount Fuji

Mount Mayon

Mount Etna

Shield Volcanoes

Shield volcanoes are large, dome-shaped mountains with gentle slopes. Although they tend not to be as tall as their stratovolcano counterparts, shield volcanoes may be very large. Shield volcanoes are mostly formed from fluid lava flows made up of basalt. Continuous eruptions can quickly create small shield volcanoes. Conversely, large shield volcanoes are formed by thousands of effusive eruptions of lava at their summits and rift zones.

It takes roughly a million years for a large shield volcano to form by this process. The summits of shield volcanoes are almost flat and often feature craters or calderas. Shield volcanoes are usually found at constructive boundaries, spreading centres, or intraplate hotspots.

Shield volcano eruptions are frequent yet are significantly gentler than the violent eruptions characteristic of stratovolcanoes. Human death or injury as a result of these eruptions are rare, but they may still destroy infrastructure and property.

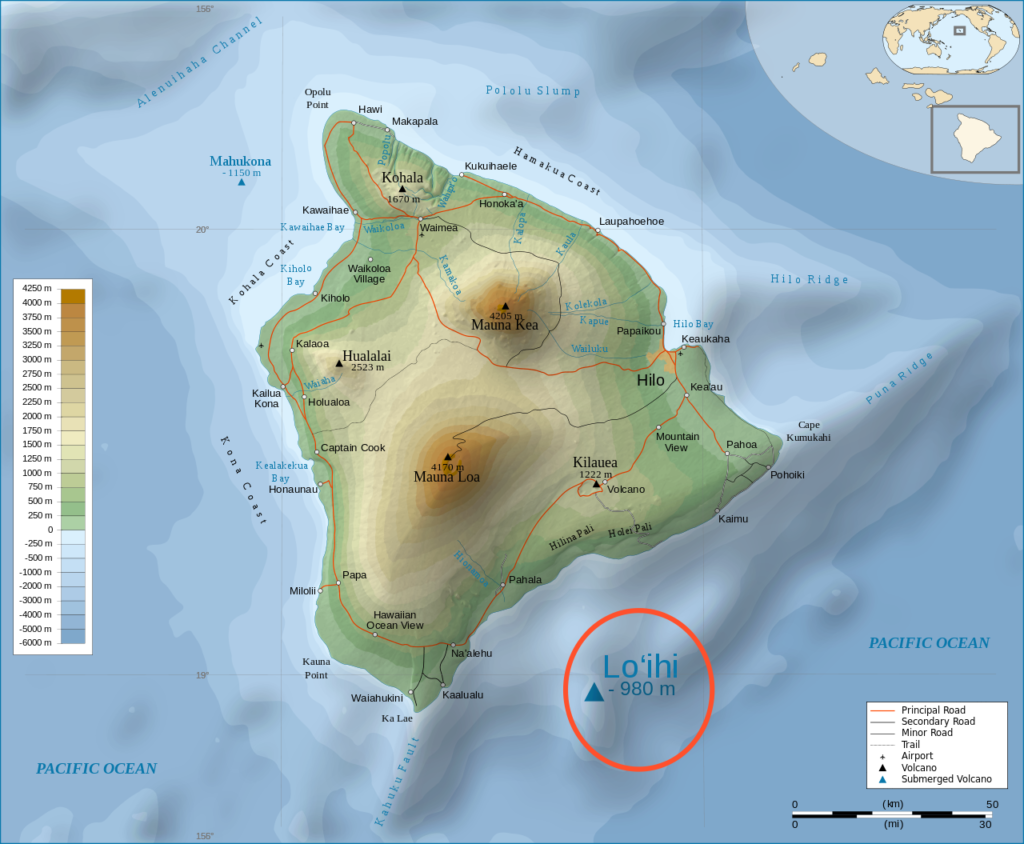

Mauna Loa and Mount Kilauea, both found in Hawaii, are famous examples of shield volcanoes. Mauna Loa is the world’s largest shield volcano, reaching more than 112 kilometres in diameter.

Mauna Loa

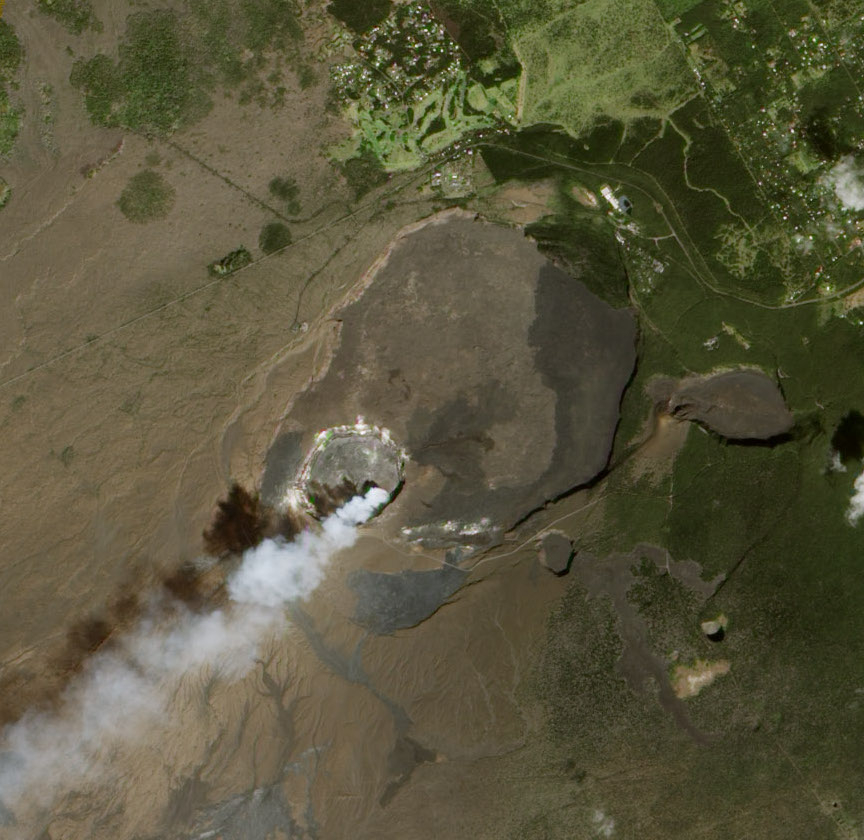

Mount Kilauea

Cinder Cones

Cinder Cones, also known as pyroclastic cones or scoria cones, are the simplest type of volcano. These small, steep volcanoes rarely go beyond 1,000 feet in height and are common in many of the world’s active volcanic regions. These volcanic landforms are often situated at the sides of larger volcanoes. Cinder cones are circular cones of hardened lava, ash, and tephra that surround a single vent. At the summit, cinder cones typically have bowl-shaped craters.

Cinder cone craters are usually located at its centre, however, strong winds can cause the crater to be upwind of the cone itself. Normally, cinder cones are only active for a limited period. However, if activity from the same vent persists for thousands of years, cinder cones may eventually develop into stratovolcanoes.

Cinder cones are built from loose pyroclastic fragments and blobs of congealed lava that erupted from a single vent. When gas-charged lava is forcefully ejected into the air, it falls apart into small cinder-sized fragments. These fragments cool sufficiently while airborne and do not meld when colliding with each other. Cinder cones are typically made of basalt or basaltic andesite. Their eruptions can range from gentle to moderately explosive.

Lava Domes

Lava domes are bulbous masses of dome-shaped viscous lava, often formed in the craters or on the flanks of stratovolcanoes. When lava is too viscous to flow, it piles up over the vent from where it extrudes. Lava domes grow as a result of expansion within the dome. While the lava outside cools down, internal intrusion of lava causes the dome to swell and steepen.

Eventually, the lava on the outside hardens and shatters, causing rocks and volcanic material to tumble down the sides. Lava domes may appear as craggy knobs or spines over a volcanic vent, or as short, viscous lava flows with steep sides known as coulees. Lava domes may also form great mounds of lava that measure many hundred metres in height and even up to a kilometre in diameter.

The lava dome found in the explosion crater of Mount St. Helens is an example of a lava dome. On the Caribbean island of Montserrat, the Soufrière Hills volcano features a lava dome complex at its summit.

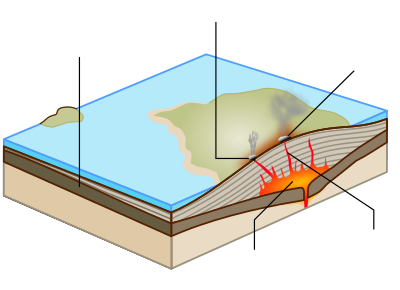

Submarine Volcanoes

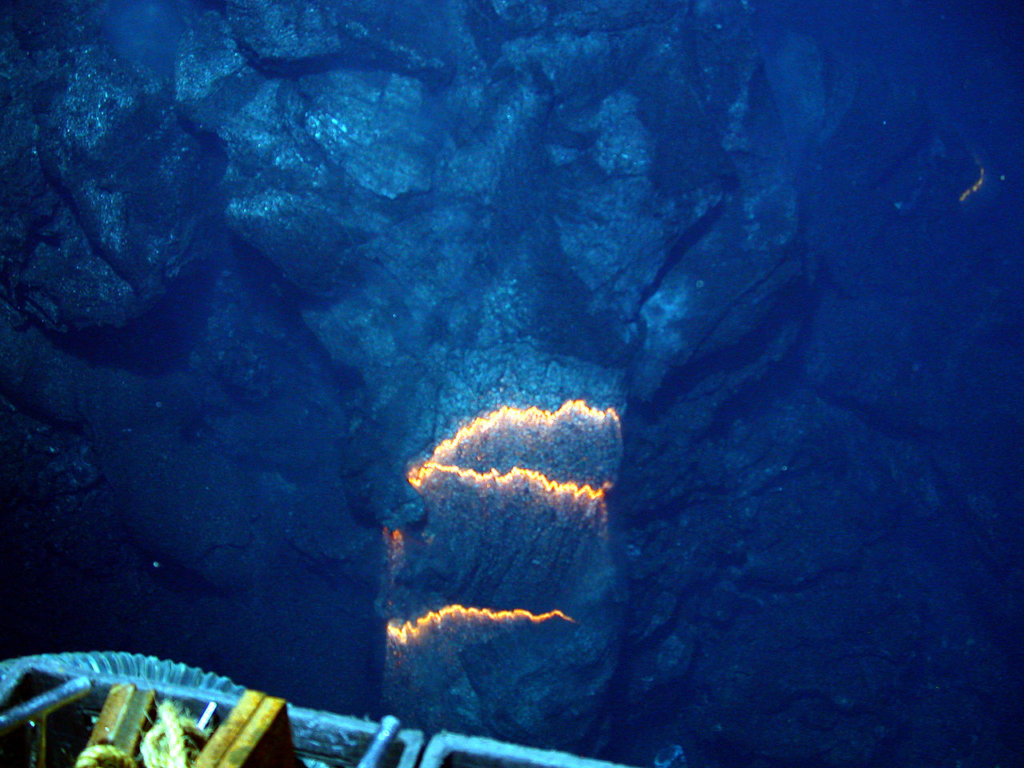

Submarine volcanoes are volcanoes that are situated underwater. Submarine volcanoes commonly form cone-shaped seamounts. However, these can also take other various forms. The majority of the active submarine volcanoes can be found in shallow depths just below sea level. These active submarine volcanoes can be detected by hydrophones that track their explosive activity.

It is predicted that active submarine volcanoes located a few thousand meters deep will become common, along with oceanic spreading centres. However, due to the high water pressure at those levels, explosive boiling is significantly reduced. This makes the eruptions of these volcanoes difficult to detect.

Seamounts can also have flat tops and come in the form of guyots. In the past, these guyots were island volcanoes that sank into the sea. However, before being submerged underwater, these island volcanoes were either eroded flat or covered with a coral cap at sea level and eventually, its supported crust cooled and became dense.

The seamount Lō‘ihi is a submarine volcano located southeast of the island of Hawaii.

Volcanic Features and Landforms

Craters

Craters are cone-shaped depressions formed as a result of explosive volcanic activity on the summit or flank of a volcano. Craters can be formed by the buildup of lava and pyroclastic material near a vent, or in a violent ejection of lava and volcanic material. During this powerful event, rock, magma, ash, and other volcanic material is sent flying out of a volcanic vent, leaving a crater in its wake.

Periods of volcanic activity can result in magma fissures breaking out from a crater’s base or walls. The entire crater floor may even be covered in molten lava during these periods.

Craters may also turn into crater lakes as a result of the natural accumulation of water. Continuing volcanic activity can cause the water in these lakes to be acidic and have high temperatures.

Calderas

Calderas are large circular or oval depressions more than one kilometre in diameter. They are formed by the inward collapse of a volcanic landform as a result of an explosive eruption that empties a magma chamber. Calderas are bowl-shaped and often have steep walls. Some calderas fill with water and form a lake. The words caldera and crater are often used interchangeably; however, calderas are considerably larger than craters.

Calderas can be created by the violent eruption of a single stratovolcano. Following an incredible explosion of gas, magma, and volcanic matter, the sheer force of the eruption blasts off the top of the stratovolcano, leaving a caldera in its wake.

Calderas may also be formed from the remains of a shield volcano. Calderas created by shield volcanoes result from the removal of magma from within the volcano. Below a volcano’s summit, large rift eruptions or lateral intrusions rid the shallow magma chambers of large amounts of magma. This causes the rock above to lose its support and collapse in on itself. Active Hawaiian volcanoes are thought to often experience this cycle of collapse and refilling of calderas, throughout their lifetimes.

Diatremes and Maars

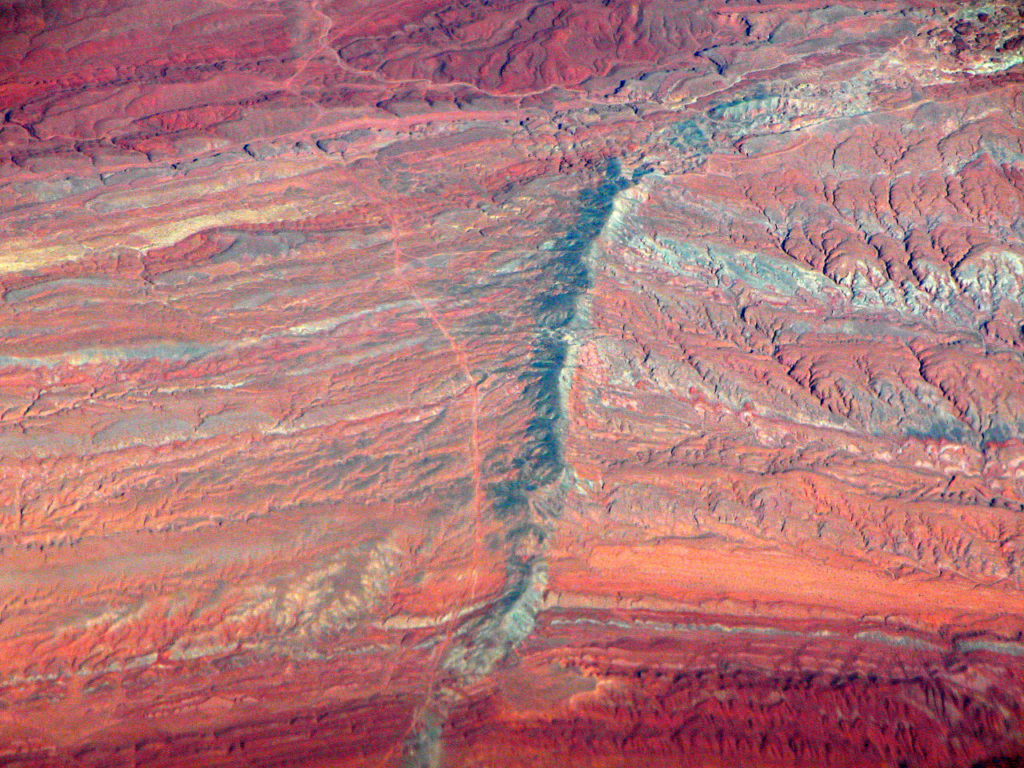

Moses Rock Dike Diatreme

Generally, a diatreme is a term that pertains to a volcanic vent or pipe engendered by the forceful exit of magma through flat-lying sedimentary rock. Magma with a high content of dissolved gas creates a powerful explosion that forces the magma upwards and through the rocks above, forming an expanded vent. As a result of this eruptive process, the sedimentary rock around a vent is melted together and lithified, and some magma intrudes into the rock.

Phreatic explosions are caused by the combination of groundwater and magma, lava, or volcanic deposits. The volatile mixture of these components leads to intense explosions of steam, ash, and other volcanic material. These explosions are closely related to diatremes.

The Three Maars at Daun

Maars are shallow craters with low reliefs and flat floors that form above diatremes. A diatreme’s violent and explosive explosion of magmatic gas or steam results in the creation of a maar above. The walls of a maar are made up of fragmented volcanic rock and the remains of the diatreme lying below it. Maars can be 60–1,980 metres wide and 9–200 metres deep. Maars are usually filled with water and form natural lakes.

Lava Flows

As the magma erupted by a volcano cools, it flows down its slopes in the form of lava. Lava can flow over great distances, albeit at relatively slow speeds. Lava can flow for over 100 kilometres at a velocity of around 48 kilometres per hour. Lava flows differ in characteristics and appearance. The chemical composition, viscosity, and eruption style are critical in determining the qualities of a lava flow.

Lava Tubes

Thurston Lava Tube, Hawaii

Long eruptions result in lava flows that continue for many hours past the initial eruption. The top and sides of these flows can eventually solidify and create a tube for liquid lava to pass through. Lava that flows through lava tubes stays liquid much longer than exposed streams because of the tube’s good thermal insulation. Lava can flow through lava tubes many kilometres past its origin. Eventually, the lava drains out and a lava tube cave remains.

Fumaroles

Fumaroles are found in places where a magma conduit passes through the water table. As a result, the magma’s heat turns water into steam. The magma can either be liquid or recently turned solid yet still retain its heat. The steam that rises to the surface is accompanied by deadly volcanic gases such as hydrogen sulfide.

The combination of steam and gas erupts from the earth through vents and fissures. The deadly gases emitted by fumaroles make them very dangerous to nearby surroundings. Fumaroles occur at the final stages of volcanic activity when magma found deep underground cools and hardens. They are also sometimes referred to as “dying volcanoes”.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is a volcano?

A volcano is a geological formation on the Earth’s surface that allows molten rock, ash, and gases to escape from below the surface, often resulting in volcanic eruptions.

What are the three main types of volcanoes?

The three main types of volcanoes are shield volcanoes, cinder cone volcanoes, and composite volcanoes (also known as stratovolcanoes).

What characterises shield volcanoes?

Shield volcanoes are characterized by their broad, gently sloping sides and relatively mild eruptions. They are typically formed by the eruption of low-viscosity lava, which flows easily and covers large areas.

What are the features of cinder cone volcanoes?

Cinder cone volcanoes are small, steep-sided volcanoes that are often composed of loose fragments of volcanic material, such as cinders and ash. They typically have a simple conical shape.

How are composite volcanoes formed, and what are their features?

Composite volcanoes are formed by alternating eruptions of lava and pyroclastic material. They have a characteristic steep profile, with layers of hardened lava, volcanic ash, and other materials. They can produce explosive eruptions.

References for Types and Features of Volcanoes

Principal Types of Volcanoes. (n.d.). Retrieved from USGS:

https://pubs.usgs.gov/gip/volc/types.html

Types of volcano. (n.d.). Retrieved from British Geological Survey: https://www.bgs.ac.uk/discovering-geology/earth-hazards/volcanoes/how-volcanoes-form/

Types of Volcanoes. (n.d.). Retrieved from Lumen: https://courses.lumenlearning.com/sanjac-earthscience/chapter/types-of-volcanoes/

Types of Volcanoes and Their Characteristics. (n.d.). Retrieved from Sciencing: https://sciencing.com/similarities-between-different-types-volcanoes-10018991.html

Volcano. (n.d.). Retrieved from Britannica:

https://www.britannica.com/science/volcano

Volcanoes. (n.d.). Retrieved from National Geographic: https://www.nationalgeographic.org/media/volcano-satellite-images/

Volcanoes, explained. (n.d.). Retrieved from National Geographic: https://www.nationalgeographic.com/environment/article/volcanoes

Volcanic Landforms: Extrusive Igneous. (n.d.). Retrieved from National Park Service: https://www.nps.gov/subjects/geology/volcanic-landforms.htm

What are the three main volcanoes?. (n.d.). Retrieved from internetgeography: http://www.geography.learnontheinternet.co.uk/topics/typesvolcanoes.html