Rainforest

Rainforests are incredibly biodiverse ecosystems that are mostly populated with evergreen trees and receive abundant amounts of rainfall. They can be found on all of the world’s continents, save for Antarctica. Tropical rainforests are also our planet’s oldest ecosystems – some have even existed in their present form for at least 70 million years. Although they only make up 6% of the Earth’s surface, they are inhabited by more than half of the world’s plant and animal species.

The largest rainforests are located near the Amazon River in South America, and the Congo River in Africa. They can also be found on the islands of Southeast Asia and some parts of Australia. Temperate rainforests exist as evergreen forests, such as those in North America and Europe.

Why “rain” forests

Rainforests have earned this name because they are partly self-watering. Through the process of transpiration, plants in the rainforest release water into the atmosphere. This moisture contributes to creating the thick, almost ever-present, cloud cover that floats over rainforests. These clouds keep rainforests warm and humid, even without rain.

Types of Rainforests

Rainforests can be classified according to two types: tropical and temperate.

Tropical Rainforests

As the name suggests, tropical rainforests are found in the tropics. More specifically, they lie between latitudes 25.5°N (The Tropic of Cancer) and 23.5°S (The Tropic of Capricorn). Tropical rainforests are located in Southeast Asia, western India, Australia, western and central Africa, Central and South America, and New Guinea.

The tropics have particularly hot and humid environments, largely thanks to the amount of sunlight that hits them almost directly. Temperatures usually stay within the range of 21–30°C. These high temperatures also keep the air hot and humid. The average humidity within these regions ranges between 77%–88%. The tropics experience high and frequent amounts of rainfall, ranging between 200–1,000 centimetres in a year. Tropical rainforests are so abundant in moisture that up to 75% of their rain is produced by their own transpiration and evaporation.

Tropical rainforests are the planet’s most biodiverse terrestrial ecosystems. A prime example is the Amazon rainforest. As the Earth’s largest tropical rainforest, it houses a plethora of the world’s species. An estimate of 40,000 plant species, 427 species of mammal, 1,300 bird species, 3,000 species of fish, and 2.5 million distinct insect species call this rainforest home.

Temperate Rainforests

Located in the mid-latitudes or temperate zones, temperate rainforests thrive where temperatures are not as hot as the tropics. Temperate rainforests are much cooler, with average temperatures ranging between 10°C–21°C. They receive significantly less sunlight and rainfall. In a year, a temperate rainforest may receive only 150–200 centimetres of rain.

Temperate rainforests are often found near coastal and mountainous areas where high amounts of rainfall are possible. However, this is considerably less than the rainfall in tropical rainforests. Rainfall in temperate rainforests is created by nearby mountains capturing warm, moisture-filled air moving in from the coast.

Although they are not as biologically diverse as their tropical counterparts, temperate rainforests have immense amounts of biological productivity. Cooler temperatures and more stable climates contribute to the reduced decomposition rate and the amassing of more biological material. This also allows many species of plants, such as redwood trees, to grow for extensive periods.

Temperate rainforests can store up to 500–2000 metric tonnes of wood, leaves, and other organic matter per hectare. For example, the North American Pacific Northwest’s old-growth forests produce biomass three times the number of tropical rainforests.

Temperate rainforests can be located in the United Kingdom, the coasts of the Pacific Northwest in North America, Japan, Chile, Norway, southern Australia, and New Zealand.

Tropical Rainforest Structure

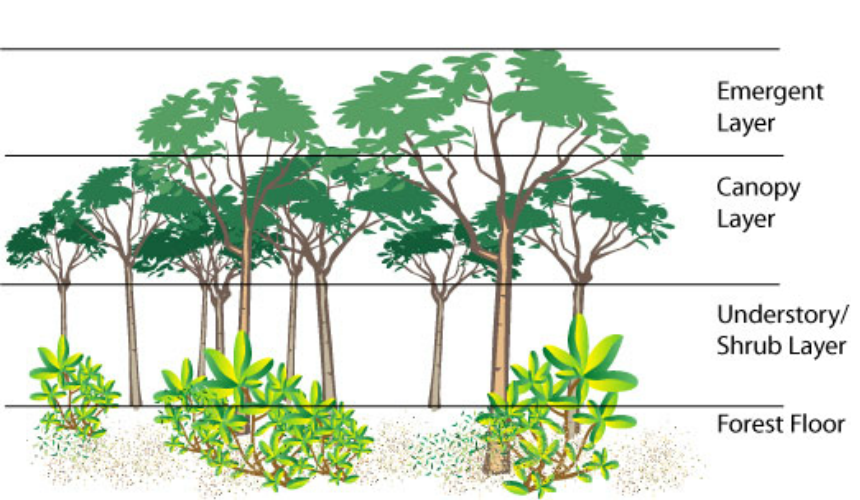

Rainforests are typically structured in four important layers: emergent, upper canopy or simply canopy, understory, and forest floor. Each layer has its own distinct characteristics that depend on variations in sunlight, air circulation, and water levels. Although each layer has a unique mix of these abiotic factors, they all belong to an interdependent system. This means that different processes and species present in one layer can affect the others.

Emergent Layer

The emergent layer is the top layer of the rainforest. Trees grow far apart and rise as tall as 60 metres, reaching far beyond the trees of the canopy. Due to intense amounts of sunlight, these plants are meant to thrive in dry conditions. The foliage is sparse on their trunks but greatly expands in the upper layer, where they absorb and photosynthesise sunlight. To avoid losing water during the drier seasons, their leaves are small and waxy. The trees in this layer rely on the wind to propagate their lightweight seeds.

Animals that live in this layer usually move about by flight or gliding. In the Amazon rainforest, such animals include bats, birds, gliders, and butterflies. The emergent layer’s apex predators include large raptors such as eagles and hawks. Animals that can’t fly are commonly small, as their weight needs to be light enough for the thinner upper branches to support them.

Notably, bats are the most diverse mammal species found in tropical rainforests. These animals fly between the three upper layers of the rainforest.

Canopy Layer

The upper canopy, or simply canopy, is the second-highest layer in the rainforest. Trees and other plants that belong to this layer reach a height of 30–45 metres tall. Unlike the emergent layer, the canopy is rich in vegetation, roughly amassing to a thickness of 6 metres. The canopy acts as a roof above the rainforest. Its dense network of leaves blocks out sunlight, rainfall, and wind.

This keeps the rainforest below dark and humid. The trees in this damp environment have evolved to have glossy leaves that repel water. With the absence of wind, trees in the canopy layer keep their seeds in their fruit. Animals eat the sweet fruit and deposit the seeds on the forest floor through their droppings.

Aside from housing the majority of the rainforest’s plant species, the canopy layer is also home to most of its animal species. Animals thrive on the canopy’s great abundance of food. In order to pierce through the muffling veil of the canopy’s leaves, different animals have adapted to using raucous, repetitive calls. Reptiles feast on the canopy’s thousands of insect species. Some creatures that live in the canopy never set foot on the forest floor.

Understory Layer

Resting several metres under the canopy, the understory is a layer darker, stiller, and even more humid than the layer above. The understory is more open than the canopy, most of its dense vegetation lies beside rivers and areas where sunlight can peek through. Shorter plants with large leaves, such as palms and philodendrons, have adapted to these low-light conditions.

The large surface areas of their leaves allow them to catch the minimal sunlight that seeps through the canopy. The plants of this layer make their flowers eye-catching and attention-grabbing. Flowers are large and clearly visible, and some even produce strong aromas to entice pollinators.

The many animal species that live in the understory take advantage of its dimly lit environment through camouflage. Many species have developed specific patterns, colours, and markings that allow them to blend in with the rainforest surroundings. An example of this is the jaguar, which has spots where its prey could confuse as leaves or specks of light. In the Congo, the green mamba is nearly indistinguishable from the surrounding foliage.

Other animals prefer the understory for different reasons. Amphibians like the vibrantly colourful tree frogs are kept moist by the understory layer’s humidity. Flying animals such as birds, bats, and insects maximise the additional airspace the understory has to offer.

Forest Floor

The forest floor is where the rainforest is at its darkest. The lack of sunlight makes it very difficult for plants to grow. The forest floor is littered with fallen leaves, dead animals, and other decaying organic material. Decomposers are surrounded by an abundance of dead organic matter and flourish in these conditions. They quickly break down the rotting material from the upper layers into nutrients. In around 6 weeks, they will have created a thin layer of humus that is rich in nutrients. The shallow roots of rainforest trees and other flora absorb these nutrients from the rich soil below.

When a tree falls, an opening is created in the canopy above, and light shines through. The forest floor teems with competition, young plants quickly race to grow and take advantage of the sunlight. After some time, these plants will fill the gap left by the fallen tree.

Decomposers such as insects are consumed by animals that roam the forest floor. Anteaters, armadillos, and wild pigs scrounge the decomposing brush for these creatures. In turn, these animals will be prey to larger predators such as big cats.

Benefits of Rainforests

The rainforests’ incredible amounts of biodiversity are essential to both human well-being and that of the environment. Rainforests play a critical role in regulating the climate and providing us with products necessary for our daily lives.

Ecological Well-being

Rainforests are critical components and contributors to the well-being of our planet. All 1.2 billion hectares of the world’s rainforests are essential in maintaining many biotic and abiotic processes necessary for all forms of life.

Among the benefits to the world’s ecological well-being is its management of the Earth’s climate. Around 20% of the world’s oxygen is produced by rainforests. Additionally, rainforests trap and store great amounts of carbon dioxide, reducing the impact of greenhouse gases. Rainforests also regulate the world’s temperature by absorbing tremendous amounts of solar energy.

Rainforests are major proponents of the maintenance of the world’s water cycle. Rainforests receive a substantial amount of precipitation, and more than 50% of this water is returned to the atmosphere through evaporation and transpiration.

As previously mentioned, rainforests also house a great number of the world’s species. As centers of biodiversity, rainforests play a key role in allowing innumerable plant and animal species to thrive. Many species are yet to be discovered, catalogued, and some species are still in need of further study.

Human Well-being

Rainforests also provide humans with various natural resources, their products and their applications. Lumber obtained from tropical wood such as teak, rosewood, mahogany, and balsa is widely used in the construction of houses. Bamboo, raffia, kapok, rattan, and other fibres are used in furniture making, weaving, insulation, and making ropes and cords. Many food products we consume originate from rainforests. A few examples are spices such as cinnamon, vanilla, ginger, and nutmeg, fruits such as bananas, mangoes, papayas, as well as cocoa and coffee beans.

Over the years, many plants in rainforests have been discovered to have medicinal properties. A quarter of all natural medicines were originally found in rainforests. Rainforest plants are currently invaluable in the field of cancer treatment and cancer research; 70% of the plants deemed effective treatments against cancer were discovered in rainforests.

Other medicinal applications of rainforest plants include steroids, insecticides, and muscle relaxants. They can also be used in the treatment and prevention of various illnesses such as asthma, arthritis, malaria, pneumonia, and heart disease. At present, only 1% of rainforest plant species have been studied for their medicinal value. This figure has important implications for the great value rainforest plants have in medicine and public health.

Threats to Rainforests

Rainforest Loss and Deforestation

Rapid human development in the last few centuries has led to great loss and destruction of rainforests worldwide. Rainforests once occupied 14% of the world’s surface, but deforestation and other harmful human processes have reduced it to 6% at present.

Agriculture, ranching, logging, mining, are all major threats to rainforest conservation. Aside from robbing these ecosystems of their natural resources, many also employ harmful mechanical techniques that further harm the environment. These lead to increased levels of erosion, destruction of natural habitats, the loss of the soil’s nutrients, and more. Unsustainable human behaviour creates near irreversible changes to the environment, making it difficult for biodiversity to return to its previous state.

Rainforest Conservation

In response to these immense threats to our planet’s well-being, many individuals, communities, governments, and international agencies have banded together for the protection and conservation of the world’s rainforests. The governments of countries with rainforests have recently advocated for the sustainable use of their rainforests. Various initiatives against illegal logging, reducing carbon emissions, and promoting the sustainable use of rainforest resources, have been enacted around the globe.

Local and international conservation groups cooperate in the protection and preservation of these natural treasures. Ecotourism has proven particularly effective in encouraging an appreciation for rainforests. Aside from educating tourists and visitors, ecotourism also provides jobs for local communities.

In Brazil specifically, many indigenous groups have come forward and staked their claim on endangered lands. These indigenous people argue that they are better stewards of these natural habitats than national governments and large corporations.

Many efforts have also been directed towards reforestation. In an attempt to rehabilitate rainforest habitats, one project, in particular, aimed to plant 73 million trees in the Amazon.

Frequently Asked Questions

Where are tropical rainforests predominantly found?

Tropical rainforests are predominantly found in equatorial regions, mainly in Central and South America, Africa, Southeast Asia, and the Pacific Islands.

What is the climate like in tropical rainforests?

Tropical rainforests have a hot and humid climate with high levels of rainfall throughout the year. The average temperatures remain consistently warm, usually between 25°C to 30°C (77°F to 86°F).

What is the biodiversity like in tropical rainforests?

Tropical rainforests are known for their exceptional biodiversity. They contain a wide variety of plant and animal species, including numerous rare and endemic species that are not found elsewhere.

What are the major threats to tropical rainforests?

The major threats to tropical rainforests include deforestation for agriculture, logging, mining, and infrastructure development. Climate change and illegal wildlife trade also pose significant challenges.

Why are tropical rainforests important for the planet?

Tropical rainforests play a crucial role in maintaining the Earth’s climate and biodiversity. They act as carbon sinks, absorbing and storing large amounts of carbon dioxide, and they provide habitats for countless plant and animal species.

References

- Rainforest . (n.d.). Retrieved from National Geographic: https://www.nationalgeographic.org/encyclopedia/rain-forest/

- Rainforests, explained. (n.d.). Retrieved from National Geographic: https://www.nationalgeographic.com/environment/habitats/rain-forests/

- Tropical rainforest. (n.d.). Retrieved from Britainnica: https://www.britannica.com/science/tropical-rainforest/Environment

- Tropical Rainforest. (n.d.). Retrieved from Internet Geography: http://www.geography.learnontheinternet.co.uk/topics/rainforest.html

- Tropical rainforest biomes. (n.d.). Retrieved from BBC: https://www.bbc.co.uk/bitesize/guides/zpmnb9q/revision/1