What are Pot Holes?

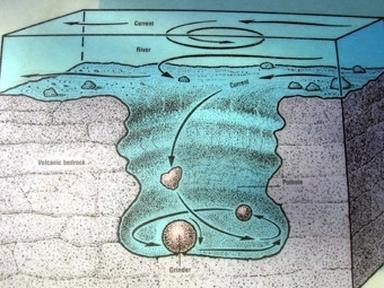

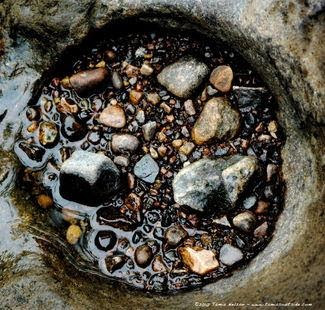

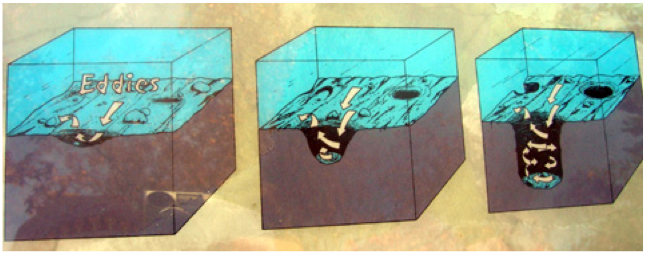

In common understanding, potholes are viewed as the impact of erosion by streams and waterways over significant periods. The common belief is that they were formed either by hard grains of sand suspended in the quickly streaming water; or by huge stones, called grinders, in the base of the pothole, tossed continually around inside by the swirling currents. The smaller grains in the swift flows are thought to have gradually worn out a depression in the stone assisted by the movement of the grinders.

Thinking about the exceptional depth of potholes, this procedure would appear to require extraordinary periods. Customary topography experiences no difficulty accepting such prolonged periods of time; however, a creationist view requires this sort of impact in only two or three thousand years, in the time passed since the Biblical flood.

The gradualness of the procedure of a scraped area by which the potholes should have been shaped appears to demonstrate the holes would have taken a long time to develop. However, this issue is intensified by the way that most potholes are arranged right now. They are sometimes a long way from the courses of streams or waterways, and many are filled with stones and sand or rubbish.

If they were formed by erosion, this process ended a long time ago. The time since they were finished, together with their present arrangement, appears to indicate an advanced age in the most recent sedimentary rocks in the earth where they happen. Potentially this is an issue for creationist geologists. How is it to be settled?

Potholes that happen a long way from streams and valleys, at times high up on slopes and mountains, are clarified by geologists as the impact of the incredible ice periods of the Quaternary. Apparently, during this time, there were potholes shaped when the ice liquefied, as waterways streamed underneath the ice and on its surface. In some cases, glacier scholars believe these surface waterways plunged down a chasm, and disintegrated the bedrock underneath, framing potholes in the most improbable spots.

The ice periods of the Quaternary are considered to have kept going from around 2,000,000 years back until around 10,000 years ago. In every one of the zones that were glaciated, there has been adequate energy for vegetation to develop after the ice dissolved. This shows that potholes on peaks and mountainsides, as they are interpreted, indicate greater estimates of the age of the world’s surface attributes.

However, systems of geologic understanding, including the flood have proposed ice ages after the flood. (Whitcomb and Morris, 1961, p. 292-303). This implies all potholes defined as the result of icy moulins shaped while the ice was spread thickly over the landmasses, and as the majority of the ice softened, trees developed, are according to interpretations, since the flood.

Potholes: Problem for Creationists

Potholes present a critical issue for creationist geologists, since they happen in the highest “strong” sedimentary strata, just as in the more established rocks. These stones are here and there related to stores of the flood. However, the nearness of potholes in them demonstrates they are, in certainty, ancient.

Will the potholes be clarified and separated from the presumption of an incredible age of the earth? Could there be another clarification of their source, aside from the one that is commonly acknowledged today? Most geologists expect that potholes have been cut by streams and waterways, by scraped area of grains of sand and stones against the bedrock. Let us investigate this understanding of the starting point, and see whether it is conceivable to represent the marvels truly.

Undoubtedly potholes frequently happen in the beds of streams and waterways. However, they are not limited to the courses of present-day streams, as they additionally happen on the beach, on slope tops, and on steeply inclining rocks where it is hard to envision any previous stream. Alexander noted (Alexander, p. 308).

They are commonly found in the beds of streams or disused stream channels. Many geologists assume that potholes were carved by streams and rivers, with grains of sand and pebbles wearing away the bedrock. We can consider the origin and see if this is possible. In Norway, many show up along the coast close to the ocean level and near the water edge.

Potholes are not restricted to stream beds. Those in the Taylor’s Falls region in Minnesota are not found throughout the waterway, yet many are on precipices high over the stream bed. Some were found only after a covering of rock had been expelled. According to Upham (Upham, 1900, p. 29):

The highest number was initially unfilled, or with just a partial filling of rounded pounding stones, residue, mud, or peat, contrasting much in their substance. Others, for the most of small size, were found filled, and some covered up by a hard store of icy float, practically ordinary till.

Close to Elk City, Idaho, gold diggers had scratched off a layer of rock from the bedrock, uncovering a few potholes. It was assumed that a river had previously streamed there. Professor George H. Stone portrayed it (Upham, p. 29):

On the slopes between Red Horse and American waterways, the diggers have washed away the overlying rock. The stone underneath the rock is specially smoothed and cleaned, yet is lopsided, containing many adjusted depressions, and potholes up to 5 feet in depth. There was an expansive river that streamed up and over slopes and valleys.

Upham likewise announced that the ‘giant’s kettles’ at Christiania, Norway (presently Oslo), when first found, were discovered covered under a layer of rock. This rock was painstakingly removed, and a record was kept of the depth and places of the stones, that were found. Upham wrote (Upham, p. 39):

On the question of the epoch or Ice Age in which the Christiania giant’s kettles were eroded, we face the presence of marine shorelines and shells deposited in the overlying glacial drifts, which indicate that during the time of the glacial recession, the land was around 600 feet lower than its present level. It is difficult to credit the moulins and potholes to a large action so far beneath the ocean level, and thus they should belong at Christiania with the earlier time of high land height and snow amassing.

Along these lines, at the well-known Christiania (Oslo) site, the potholes were discovered covered under a layer of rock. This is common to numerous pothole discoveries. One was unearthed from under a house in Buffalo, N.Y. A comparative discovery prompted the improvement of Glacier Gardens, in Lucerne, Switzerland. Alexander wrote (Alexander, p. 305):

Two generations of voyagers have marvelled at the extraordinary potholes of the Glacier Garden at Lucerne, Switzerland. A group of potholes was found in 1872 during excavations for a basement in a glacier. Later the float was removed, revealing more than 30 irregularly grouped holes in waterworn and striated bedrock.

It is reasonable to assume, when potholes are found under a layer of rock and sand, that there was a previous waterway in the region, at the same time, since numerous potholes are found deeply buried a long way from waterway courses; and, would it not be similarly reasonable to assume, since these potholes were discovered apart from the course of any stream, that their arrangement has nothing to do with ebbs and flows and stream erosion?

What is more, those that happen in the courses of streams today probably will not have been cut out by the present stream, and only uncovered when the ebb and flow cleaned out the loose sand. A similar procedure, of washing the bedrock clean of layers of rock, would clarify the proximity of the potholes to the coastline. They were there already, covered under a layer of sand and gravel until the waves washed over the bedrock and uncovered the potholes.

For if the ocean had been beating the shores where the bedrock was secured with a slight layer of rock, the sand would be washed away soon and the underneath forms revealed, including potholes. The water would not have cut them out, only uncovered them. The same principle applies to rivers.

Reasonable Cause: Water Erosion?

It is fascinating that with regards to the geologic observation of potholes, there is no reference that does not connect them with flows and erosion. That potholes are carved by abrasion in rivers, is an accepted truth. Anyway, as improbable as it might appear, it is unquestioning assumed that in any place potholes are discovered, it is likely that they were caused by a river, even where they happen at the highest points of slopes or cliffs.

An example of this is near Archbald, Pennsylvania, where, in 1884 and 1885, two huge potholes were found while coal mining was underway. Below around 15 feet of debris, the central hole was cleared and reached 38 feet deep, around 15 feet wide at the base, expanding to a limit of 42 feet, and a width of 24 feet over the top. The second pothole expanded to about 50 feet in the bedrock (Upham, p. 38). Another unusual case of potholes on high slopes was referenced by (Alexander, p 312):

For such potholes as those on the high quartzite feign east of Devil’s Lake, Wisconsin, it must be accepted either that this bluff was s glaciated, which it was not, or that some old stream flowing several feet over the present lake level over the then-covered quartzite edge eroded the holes in rapids coursing down its southern slant.

Regardless of how implausible it might appear, most geologists expect that waterways have consistently formed potholes; yet it is possible to assume, that since potholes happen in territories that were probably never at any point the site of a stream, their development is not identified with waterway activity.

Rather than expecting that potholes were probably cut by erosion in rivers, let us attempt to be objective and decide if the realities confirm this supposition. As has appeared, examples of pothole distribution do not confirm it. They happen in regions where it appears far-fetched that a stream could have existed.

Read more about Coastal Landforms

Frequently Asked Questions

What are potholes and how do they form?

Potholes are cylindrical depressions in rock formed by the abrasive action of water-borne sediment and pebbles as they swirl in eddies in streams.

Where are potholes commonly found?

Potholes are often found in riverbeds, particularly in fast-flowing and turbulent sections of streams and waterfalls.

How do potholes contribute to landscape evolution?

Potholes contribute to erosion and widening of river channels, altering the landscape over time.

Can potholes be used as indicators of past environmental conditions?

Yes, the presence of potholes can provide insights into past river dynamics, flow rates, and sediment characteristics.

How can potholes be preserved for educational and geological purposes?

Preserving potholes involves protecting their natural environment, restricting human activities that could damage them, and creating educational resources.

References

- On the Interpretation of Potholes. (n.d.). Retrieved from creation concept: https://creationconcept.info/pothart.html

- Pothole Landforms. (n.d.). Retrieved from World and Landforms: http://worldlandforms.com/landforms/pothole/

- Potholes. (n.d.). Retrieved from geo.mtu,edu: http://www.geo.mtu.edu/KeweenawGeoheritage/The_Fault/Potholes.html

- River Landforms. (n.d.). Retrieved from weebly: http://thebritishgeographer.weebly.com/river-landforms.html

- River Potholes: Modern and Ancient. (n.d.). Retrieved from Digital commons: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1048&context=diffendal

- The relationship between diameter and depth of potholes eroded by running water. (n.d.). Retrieved from ScienceDirect: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1674775518301495

- Alexander, H. S. 1932. Pothole erosion, Journal of Geology, 40 ( 4 ): 305-337.

- Barbour, 1. G. 1971. Issues in science and religion. Harper & Row, Publishers, N.Y., London. Paperback edition, p. 139.

- Fairbridge, R W. Editor. 1968. Encyclopedia of geomorphology. Reinhold Book Corp., N.Y.

- Foster, R. J. 1971. Physical geology. Chas. E. Merrill, Publishers, Columbus, Ohio.

- Hanson, N. R. 1958. Patterns of Discovery. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- Higgins, C. G. 1957. Origin of potholes in glaciated regions, Journal of Glaciology, 3 (21):11-12.

- Morris, H. M. 1974. Diversity of opinions found in Creationism, Creation Research Society Quarterly, 11(3):173-175.

- Stone, G H. 1900. Note on the glaciation of Central Idaho, American Journal of Science, Fourth series, 9 ( 49 ):9-12.

- Upham, W. 1900. Giant’s kettles eroded by moulin torrents, Bulletin of the Geological Society of America, Vol. 12, pp. 25-44.

- von Engeln, 0. D. 1942. Geomorphology. Macmillan Co., N.Y.

- Whitcomb, J. C. and H. M. Morris. 1961. The Genesis Flood. The Presbyterian & Reformed Publishing Co., Philadelphia, Pa..