Origin and advancement of landforms of mid and low-latitude deserts

When it comes to hot deserts, their immense size, the absence of surface vegetation, and the movement of millions of sand particles into massive landforms can create fantastic desert landforms.

Aeolian (wind) erosional highlights

•Deflation hollows: Land depressions, known as deflation hollows, have been created in a portion of the world’s biggest deserts by the erosional process of deflation. Dew gathers in low-lying basins, giving a contribution of dampness. The surface material is then broken by chemical weathering and moved away on the breeze. A portion of the deflation hollows in the Sahara Desert is several kilometers wide. The biggest is the Qattara Depression in Egypt, which, at its most profound point, is 134 meters beneath the ocean level. The American Mid-West Dust Basin of the 1930s was framed as a result of deflation, following an extremely dry season that made the dirt dry, friable and inclined to wind erosion. In the case of erosion in the American Mid-West, the dynamic harmony (the inclination towards a specific condition of parity) was irritated with an extraordinary occasion, right now, however, it could without much of a stretch be a storm or floods. Human movement can likewise make interruption the dynamic balance, for example, by adjusting the seepage basin.

•Desert asphalts: Covering gigantic zones, desert asphalts or ‘reg’ are flat, stony surfaces that look like a cobbled road. Any sediment measured, or sand-sized particles have been blown and moved somewhere else. The desert surface speaks to all the particles that are too huge to be lifted by the breeze possibly and can be a proportion of wind quality (the more significant the prevailing dregs abandoned – the more grounded the breeze).

•Ventifacts: Individual rocks and stones are regularly the concentration for wind erosion. Sand in suspension causes scraped spot and pitting as an afterthought confronting the prevailing breeze. Scraped spots can smooth one side of a stone and produce irregular sandblasted shapes.

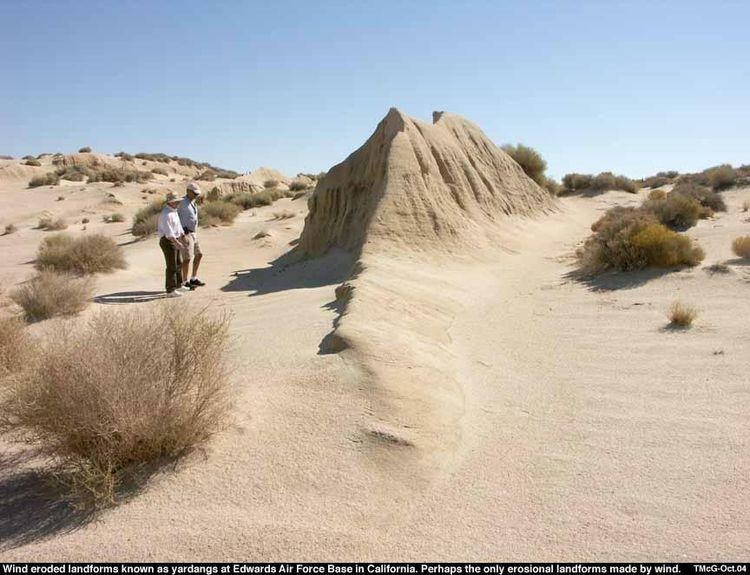

•Yardangs: Extensive edges of rock known as yardangs, isolated by grooves (troughs), can shape in arrangement to the predominant breeze heading. These edges are typically three to multiple times longer than they are wide. Solid breezes blowing one way and conveying sand in suspension disintegrate the desert surface by scraped area. Gentler rocks dissolve quicker than harder rocks, so edges of progressively safe rocks stay upstanding. In parts of the Arabian, Saharan and Atacama Deserts, yardangs are sufficiently huge to be noticeable on satellite symbolism.

•Zeugen: this is another landform etched by wind erosion. They are long tabular (square moulded) masses of safe stone isolated by channels and are framed in zones where progressively safe stone overlies less safe rocks. The overlying rocks are endured, and the breeze slices vertically through the top, uncovering the hidden gentler stone, which is then disintegrated all the more quickly. Zeugens can be anyplace somewhere in the range of five and 30 meters in tallness.

•Rock pedestals: These mushroom-moulded rocks structure because of sand impacting. Sand particles skip over the desert surface passed up solid breezes and scrape anything in their way. Sand impacting is best inside the first 1.5 meters of the ground surface, and this implies there is a critical undermining of the base of vertical rocks. Proceeded with the erosion of the ‘stalk’ can prompt the possible breakdown of the platform. Fantastic stone platforms are found in Utah, USA and the White Desert in Egypt.

Aeolian depositional highlights

At the point when sand grains shipped by saltation are stored, they structure sand ridges as the breeze eases back down. Wind can slow down for various reasons, yet it is typically vegetation, rocks or other sand ridges making a deterrent. Sand ridges structure in various shapes and formats subordinate upon various elements:

•The bearing and speed of the breeze

•The amount of sand being shipped

•The nature of the desert surface

•The nearness of vegetation

•Erg: A vast zone of sand ridges is known as an erg (sand ocean). These highlights can extend for many kilometers and spread roughly one-fourth of every single dry district. Ergs are, for the most part, kept to the Arabian and Sahara Deserts. Sand oceans are an adept name for a vast region of sand rises because of how that sandhills seem like a moderate moving wave as they move with the breeze. Five fundamental rise shapes have been perceived: crescentic, direct, star, vault and illustrative.

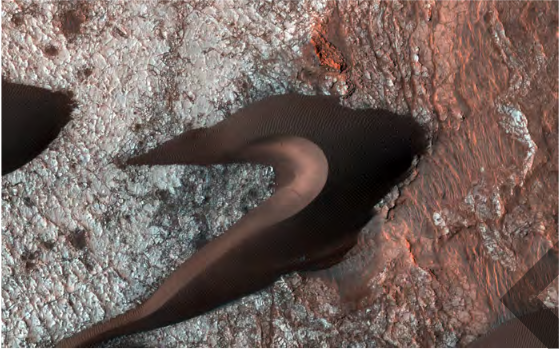

•Barchan dunes: The barchan is a sickle formed ridge that can arrive at 30m high and is moved by the breeze. Saltation and surface downer happen on the delicate upwind-confronting incline of the hill (stoss face) as the breeze pushes material upslope. Silt at that point, consistently torrential slides over the edge and down the more extreme lee (slip face) of the sand ridge, pushing the whole sand rise ahead at a pace of up to 30m/yr. Whirling wind flows (vortexes) help to keep the lee slant soak. The horns (edges of the hill) move quicker than the focal point of the ridge as there is less sand to move. The barchan ridge underneath is entirely Mars!

•Seif dunes: these are longitudinal rises (named after an Arab bent sword) that are long edges of sand which structure corresponding to the overall breeze. They are a lot bigger and more typical than barchan ridges. Seif (straight) rises can arrive at 200m in stature and over 100km long. They are structured from connected barchan ridges when a brief – yet rehashed – alter in twist course happens. This leads to the horns or ‘arms’ of a barchan hill to extend and converge with its neighbouring rise to frame a progression of associated rises. These hills are prevailing in South East Libya and southwest Algeria.

Picture of a Martian barchan ridge taken by the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter: NASA/JPL/Uni of Arizona

Water (fluvial) landforms

Although storms are inconsistent in desert territories, a torrential downpour can be exceptionally erosive, changing the scene drastically, bringing residue down from desert mountains, reshaping waterway beds and storing flotsam and jetsam in alluvial fans, bahadas and chotts. These are classed as fluvial processes and landforms as unmistakable from aeolian or ‘windblown’ processes and highlights.

Erosional highlights

•Inselbergs: Meaning ‘island slope’ (German), inselbergs are secluded soak sided slopes including plateaus and buttes that are leftovers of the erosion process upon broad desert surfaces leaving masses of progressively safe stone as heritage includes in a brought down plain. Plateaus are level like mountains and buttes are confined column like developments. There is an incredible discussion about the conditions under which inselbergs structure. Numerous geomorphologists presently accept that they are relict uplands of past climatic conditions when precipitation was higher and had significantly more capacity to dissolve the milder stone encompassing inselbergs, by water erosion. Uluru (Ayers Rock) is an inselberg in Australia.

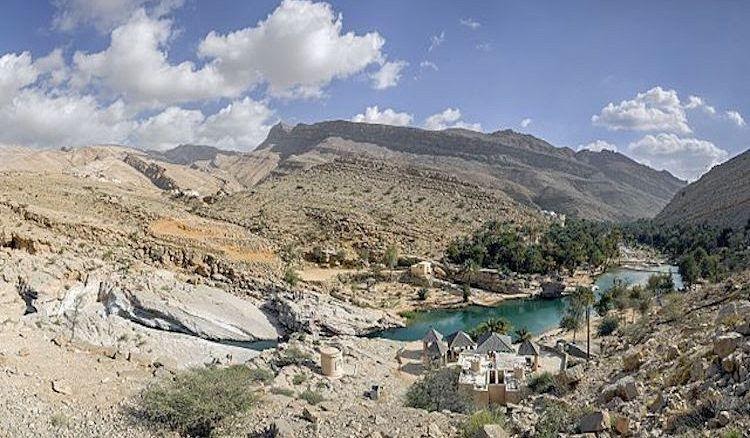

•Wadis: Dry waterway valleys, known as aqueducts, are dry for the more significant part of the year and load up with water streaming in vaporous streams after a torrential downpour. Aqueducts can form into profound gorges and chasms on the off chance that quick streaming deluges of water more than once dissolve them.

Depositional highlights

The primary depositional highlights made by streaming water in desert scenes can be found inside intermountain basins or desert pediment.

•Pediments: these are delicate slanting territory situated at the foot of desert mountain ranges with a low slant point (somewhere in the range of 1° and 7°) comprising both solid base stone, gradual depositional additions, or a blend of the two. They speak to the intersection between a zone of soak slants and erosional processes (uplands) and level, depositional marshes. They are framed by the scraped spot of rock by the residue conveyed in sheet floods and are typically canvassed in a slight layer of silt speaking to the remaining parts of the last flood.

•Alluvial fans: these are delta-like depositional landforms that create where a transient stream runs over a break of incline to a shallower angle, causing vitality misfortune and the considerable deposition of the dregs conveyed. The kept residue spreads out into a fan shape, the most substantial being dropped first. Alluvial fans can be somewhere in the range of 20 km long and 300 m in thickness. The pediment frequently frames the break-in slant, at which point the testimony of discrete (individual) alluvial fans happens.

•Bahadas (Bajadas – Spanish for ‘slope’): Where various equal aqueducts combine at a mountain front in nearness, several alluvial fans mix with those neighbouring on either side, framing a bahada/bajada. These bahadas can conceal mountain pediments, or structure at the foot of them where the slope turns out to be practically level.

•Chotts: Chotts (North Africa), sabkhahs (Arabian Peninsula) and playas (North America) or dish (Australia) are, for the most part, names for salt lakes or their dissipated stores. These highlights are incredibly regular in deserts and have various ordinary qualities:

Read more about Desertification

They highlight at the depressed spots of the desert scene

They are typically exceptionally level

They have no outlet to the ocean

Ephemeral water gathers in them after overwhelming precipitation

Evaporation prompts the development of salt container or thick hulls of salt, and other vanish stores

Vegetation is meager because of the salt abandoned after evaporation of the transient water

•Chott Ech Chergui, an enormous endorheic Salt Lake in Saïda Province, Algeria and even though vegetation, is scanty, has been assigned a Ramsar wetland of universal significance for various compromised and helpless creature and plant species.

The connection between process, time, landforms and scenes in mid and low scope desert settings: trademark desert scenes.

A significant number of our present-day deserts were once a lot of wetter, fertile fields and timberlands before. A portion of the proof for this incorporates stores of groundwater under the Sahara, old soil skylines and relict landforms, for example, plateaus and buttes in Utah, USA. Eight thousand years before the northern side of the equator had a wetter atmosphere, rainstorm increased, and the Sahara experienced sticky conditions. During the Holocene Climate Optimum (9000-4000 BC), Lake ‘Uber Chad’ was several kilometers wide with individuals chose its shores. In Sudan, Wadi Howar, a once relentless waterway, continued fish and crocodiles just as farming and human settlement and in south-east Algeria, rock compositions show savannah animals, for example, elephants and zebus (dairy cattle). It is imagined that the drying of Sahara from savannah to desert started around 5,500 years prior and was brought about by a move in the Earth’s circle. This implies the present desert scene is an aggregation of a period arrangement of landforms and scenes, some of which were shaped under past climatic conditions however are as yet apparent, some that have been creating over ongoing centuries (a large number of years) yet are persevering, some in the course of the remaining century, and others that are very brief highlights yet that are in presence during contemporary conditions.

Frequently Asked Questions

How are sand dunes formed in hot deserts?

Sand dunes form when wind carries sand grains, depositing them in mounds and ridges. Over time, dunes migrate and change shape due to wind direction.

What is desertification, and how does it occur?

Desertification is the process of fertile land becoming desert due to factors like deforestation, overgrazing, and unsustainable agricultural practices.

How do desert plants and animals adapt to the harsh environment?

Desert plants have water-conserving features like reduced leaves and deep root systems, while animals have adaptations like nocturnal behaviour and water storage.

What are flash floods, and why are they common in hot deserts?

Flash floods occur when heavy rainfall overwhelms the arid soil’s ability to absorb water. Lack of vegetation and steep terrain in deserts contribute to their occurrence.

How do temperature fluctuations impact hot desert landscapes?

Extreme temperature variations between day and night can cause rocks to expand and contract, leading to weathering and erosion processes like exfoliation.

References

- Arid landform development. (n.d.). Retrieved from Arid landform development: https://s3-eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/tutor2u-media/resource-samples/AQA-A-Level-Geography-Core-Resource-Pack-Deserts-Sample.pdf?mtime=20170216084728

- Bahadas. (n.d.). Retrieved from Revision Online: https://revision.co.zw/wadisbahadas-and-the-desert-piedmont-zone/

- Barchan Landforms. (n.d.). Retrieved from World Landforms: http://worldlandforms.com/landforms/barchan/

- Desert Asphalt. (n.d.). Retrieved from Pixnio: https://pixnio.com/nature-landscapes/road/road-sand-travel-asphalt-barren-desert-highway

- Erosional Landforms ( Deflation hollows and caves) and Depositional Landforms(Sand dunes). (n.d.). Retrieved from UnAcademy: https://unacademy.com/lesson/erosional-landforms-deflation-hollows-and-caves-and-depositional-landformssand-dunes/HGF2UJZU

- Fluvial Landforms: What Is Wadi? (n.d.). Retrieved from World Atlas: https://www.worldatlas.com/articles/fluvial-landforms-what-is-wadi.html

- Tropical Desert. (n.d.). Retrieved from Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tropical_desert

- Yardang. (n.d.). Retrieved from epod: https://epod.usra.edu/blog/2004/11/yardang.html