What are Biomes?

The biome idea composes an enormous scope of biological variety. Global biomes are recognized basically by their overwhelming vegetation and are principally dictated by temperature and precipitation.

Terrestrial Biomes

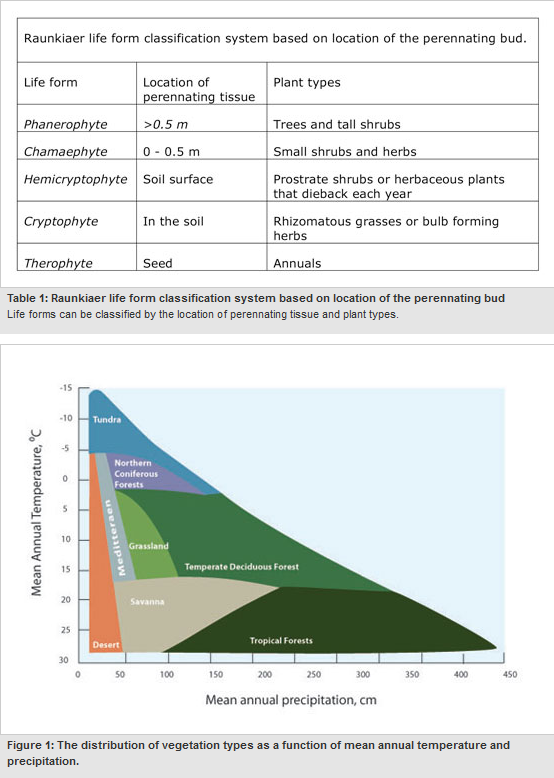

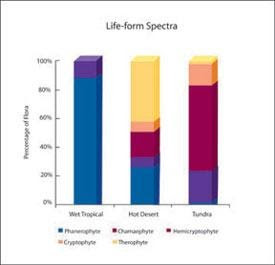

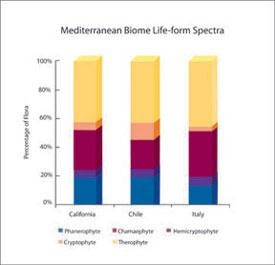

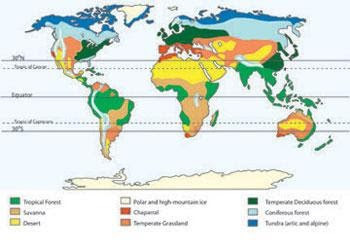

Contrasts in temperature or precipitation decide the sorts of plants that develop in a given region (Figure 1). As a rule, stature, thickness, and species assorted variety diminish from warm, wet atmospheres to cool, dry atmospheres. Raunkiaer (1934) characterized vegetation structures dependent on characteristics that differed with the atmosphere. One such framework depended on the area of the perennating organ (Table 1). These are tissues that offer ascent to the new development the accompanying season and are consequently touchy to climatic conditions. The general extents of various living things change with the atmosphere (Figure 2). Life structure spectra are all the more indistinguishable in comparable atmospheres on unexpected mainlands in comparison to they are in various atmospheres on a similar landmass (Figure 3). Areas of comparative atmosphere and popular plant types are called biomes. This part depicts a portion of the significant earthly biomes on the planet; tropical forests, savannas, deserts, calm fields, mild deciduous forests, Mediterranean clean, coniferous forests, and tundra (Figure 4).

Table 1: Raunkiaer life structure arrangement framework dependent on the spot of the perennating bud

Living things can be arranged by the area of perennating tissue and plant types.

The dispersion of vegetation types as an element of mean yearly temperature and precipitation.

Tropical Forest Biomes

Figure 2: Life-structure spectra in various atmospheres

Raunkiar ordered vegetation frames on characteristics that differed with the atmosphere, for example, the perennating organ or tissues that offer ascent to the new development the accompanying season.

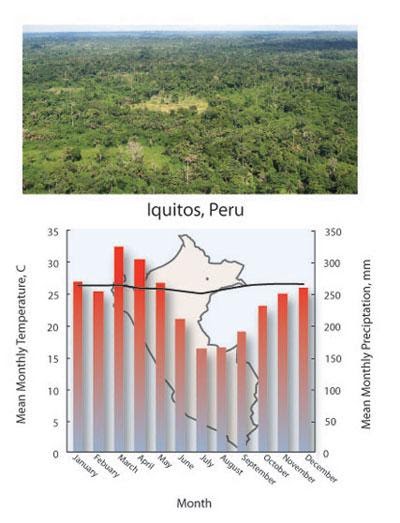

Tropical forests are found in zones fixated on the equator (Figure 4). Focal and South America have half of the world’s tropical forests. The atmosphere in these biomes shows occasional minimal variety (Figure 5), with high yearly precipitation and moderately consistent, warm temperatures. The predominant plants are phanerophytes – trees, lianas, and epiphytes. Tropical rainforests have an emanant layer of tall trees more than 40 m tall, and overstory of trees up to 30 m tall, a sub-shade layer of trees and tall bushes, and a ground layer of herbaceous vegetation.

Tropical forests have unique biodiversity and essential profitability of any of the global biomes. Net essential efficiency ranges from 2–3 kg m-2 y-1 or higher. This high efficiency is continued despite intensely drained, supplement poor soils, as a result of the high deterioration rates conceivable in damp, warm conditions. Litter breaks down quickly, and fast supplement take-up is encouraged by mycorrhizae, which are contagious mutualists related to plant roots.

The tropical forest biome is evaluated to contain over a portion of the earthbound species on Earth. Roughly 170,000 of the 250,000 depicted types of vascular plants happen in tropical biomes. Upwards of 1,209 butterfly species have been archived in 55 square kilometers of the Tambopata Reserve in southeastern Peru, contrasted with 380 butterfly species in Europe and North Africa consolidated.

The tropical forest biome is made out of a few distinctive sub-biomes, including evergreen rainforest, occasional deciduous forest, tropical cloud forest, and mangrove forest. These sub-biomes create because of changes in regular examples of precipitation, height or potential substrate.

Savanna Biomes

Figure 3: Life-structure spectra in comparative Mediterranean sort atmospheres on various landmasses

Life-structure spectra are all the more indistinguishable in comparable atmospheres on unexpected landmasses in comparison to they are in various atmospheres on a similar mainland.

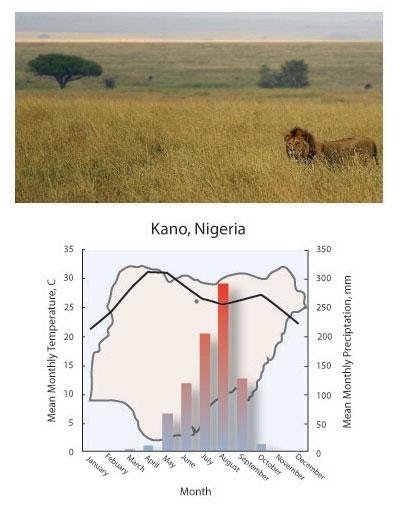

In the north and south of tropical forest, one can see that biomes are savannas (Figure 4), with lower yearly precipitation and longer dry seasons (Figure 6). These biomes are ruled by a blend of grasses and little trees. Savannas spread 60% of Africa and speak to a change from tropical forests to deserts. Trees in savannas are usually dry season deciduous. A few savanna types related to varying precipitation designs, the stature of the water table and soil profundity can be recognized by their general plenitude of trees and grass.

Dreary dry season fires have happened in the African savanna in the course of the most recent 50,000 years. Fire assumes a significant job to be decided among trees and grasses in savannas. With extensive stretches between flames, tree and bush populaces increment. Flames discharge supplements tied up in dead plant litter. Soil gives a decent warm protector, so seeds and subterranean rhizomes of grasses are generally shielded from harm.

Net essential profitability ranges from 400–600 g m-2 yr-1, yet fluctuates relying on nearby conditions, for example, soil profundity. Decay is fast and all year and the yearly turnover pace of leaf material is high; up to 60–80%. This turnover is helped by the decent wide variety of enormous herbivores found in savannas, where up to 60% of the biomass can be expended in a given year. Waste scarabs are significant segments of the supplement cycle because of their job in separating creature droppings. The high herbivore decent variety and creation are reflected by the extraordinary assortment of predators and foragers found in savannas.

Desert Biomes

Figure 4: Biomes of the world

Biomes are areas of comparative atmosphere and popular plant types.

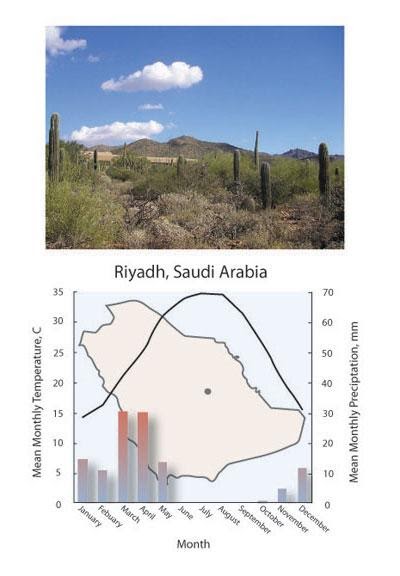

Deserts by and large happen in a band the world over between 15–30° N and S scope (Figure 4). They spread between 26–35% of the land surface of the Earth. The atmosphere of deserts is ruled by low precipitation, by and large underneath 250 mm yr-1 (Figure 7). There is a ton of inconstancy in desert types, with hot deserts, cold deserts, high rise deserts, and downpour shadow deserts. Like this, there is much variety in the biodiversity, efficiency and living beings found in various kinds of desserts.

The predominant plant biomass in many deserts is made out of perpetual bushes with deep roots and little, dim or white leaves. In any case, in warm deserts, therophytes (yearly plants) can make up the majority of the species’ assorted variety (Figure 2). Desert annuals can endure eccentric dry periods as seeds. Seeds may stay feasible in the dirt for quite a long while until the suitable precipitation and temperature conditions happen, after which they will grow. These annuals develop quickly, finishing their life cycle in half a month, at that point blossoming and setting seed before soil water saves are drained. Winter desert annuals in North American deserts can produce more than 1 kg m-2 of biomass in a wet year.

Except for the enormous sprouts of annuals, net essential profitability in many deserts is a low and very factor. There is a definite connection between efficiency and precipitation, and qualities can go from close to 0 to 120 g m-2 yr-1. Similarly, likewise, with savannas, profitability will shift with soil profundity and nearby waste examples (e.g., washes).

Tropical forest biome atmosphere outline

Figure 5: Tropical forest biome atmosphere outline

The atmosphere in these zones shows occasional minimal variety with high yearly precipitation and generally steady, warm temperatures.

Field Biomes

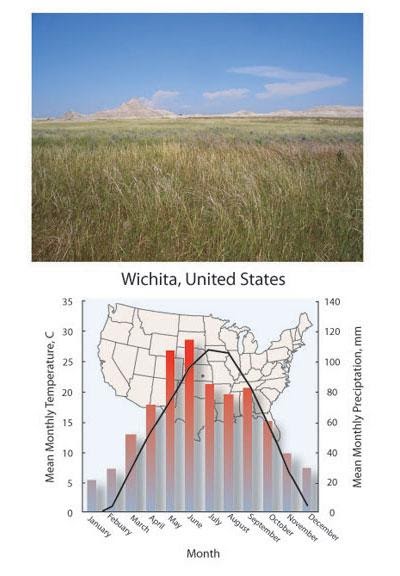

Field biomes happen mainly in the insides of mainlands (Figure 4) and are portrayed by huge occasional temperature varieties, with sweltering summers and cold winters (Figure 8). Precipitation fluctuates, with a solid summer top. The sort of field network that creates, and the profitability of meadows, rely unequivocally on precipitation. Higher precipitation prompts tallgrass prairie with high biodiversity of grasses and forbs. Lower precipitation prompts short grass prairies and dry fields.

Savanna biome atmosphere chart

Figure 6: Savanna biome atmosphere chart

Savannas are found north and south of tropical forest biomes and are portrayed by lower yearly precipitation and longer dry seasons.

Net essential efficiency in dry meadows might be 400 g m-2 yr-1, while higher precipitation may bolster up to 1 kg m-2 yr-1. Fields grade into deciduous forest biomes on their wetter edges, and deserts on their drier edges. The outskirts among prairies and different biomes are dynamic and move as per precipitation, aggravation, fire and dry spell. Fire and the dry spell will support field over forest networks.

Desert biome atmosphere outline

Figure 7: Desert biome atmosphere outline

There is a unique changeability in desert types, with hot deserts, cold deserts, high rise deserts, and downpour shadow deserts.

Three significant specific powers overwhelm the development of plant qualities in meadows, repeating fire, intermittent dry spell, and eating. These components have prompted the strength of hemicryptophytes in meadows with perennating organs situated at or beneath the dirt surface. Numerous grasses have subterranean rhizomes associating over the ground shoots or tillers. Grass cutting edges develop from the base up, with effectively isolating meristems at the base of the leaf. Hence when slow eaters eat the grass cutting edge, the meristem keeps on separating, and the sharp edge can keep on developing. Grasses are often decay-resistant and repeating cool, quick-moving surface flames began by lightning toward the finish of summer help in supplement reusing: Flames animate efficiency and the germination of heatproof seeds.

Field biome atmosphere outline

Figure 8: Grassland biome atmosphere graph

Field biomes happen principally in the insides of mainlands and are described by enormous regular temperature varieties, with sweltering summers and cold winters.

A large number of the world’s biggest earthly creatures are found in meadows. Creatures, for example, dim kangaroos (Macropus giganteus) in Australia (Bison bonasus) and ponies (Equus spp.) in Eurasia and North America, animal varieties rich arrays of touching creatures, their predators, and scroungers are found. Leftover groups in North America recommend that unsettling influences because of slow eaters expanded neighbourhood biodiversity by making openings that uncommon species could colonize. Huge slow eaters additionally quickened plant deterioration through their droppings, making supplement hotspots that modified species creation.

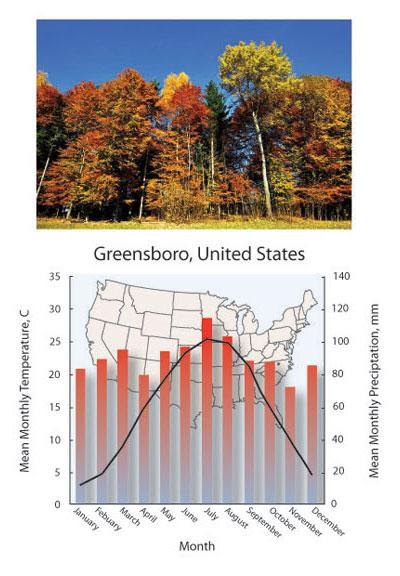

Temperature Deciduous Forest Biome

Temperature deciduous forests happen in mid-scopes (Figure 4) where cold winters, warm summers, and high all year precipitation happens (Figure 9). Net essential profitability ranges from 600–1500 g m-2 yr-1 with high litter creation. Litter fills in as a significant pathway for supplement reusing. This biome is named for the predominant trees that drop their leaves throughout the winter months. These forests may have an overstory of 20–30 m tall trees, an understory of 5–10 m trees and bushes, a bush layer around 1–2 m in tallness, and a ground layer of herbaceous plants. Biodiversity is moderately high right now to the specialty apportioning permitted by the numerous forest layers. Progressively mind-boggling forests are related to a unique number of creature species; for instance, winged animal species assorted variety shows a positive connection with forest tallness and number of layers.

Mild deciduous forest atmosphere graph

Figure 9: Temperate deciduous forest atmosphere chart

Temperature deciduous forests happen in mid-scopes and are portrayed by cold winters, warm summers, and high all year precipitation happens.

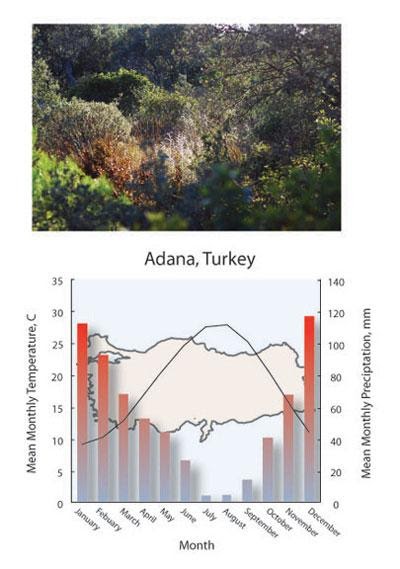

Mediterranean Climate Biomes

This little biome (about 1.8 million square km) is isolated into five separate districts between 30–40 degrees N and S scope (Figure 4) with blistering, dry summers, and cold, damp winters (Figure 10). Random evergreen, sclerophyllous bushes and trees have developed autonomously in every one of these zones, speaking to a striking case of merged advancement. Net essential efficiency changes from 300–600 g m-2 yr-1, subordinate upon water accessibility, soil profundity, and age of the stand. Stand profitability diminishes following 10–20 years as litter and woody biomass collects. Repeating fires help in supplement cycling, and numerous plants show fire-actuated or fire-advanced blooming. A few animal categories can resprout from buds secured by the dirt, while others sprout from decay-safe seeds that lie torpid in the dirt until a fire advances their germination. Therophytes make up a considerable part of the vegetation, and their appearance is related to openings made by flames.

Mediterranean biome atmosphere outline

Figure 10: Mediterranean biome atmosphere outline

There are five separate areas between 30-40 degrees N and S scope with sweltering, dry summers, and cold, soggy winters.

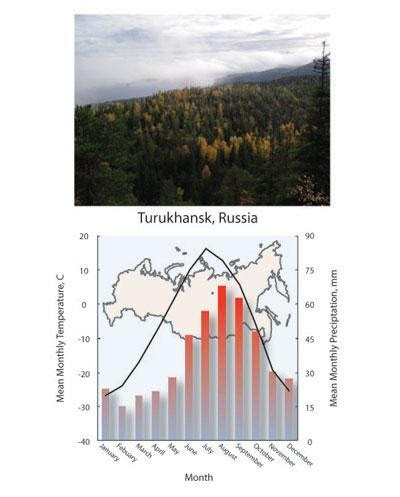

Northern Coniferous Forest Biome

Situated at higher scopes is a biome ruled by needle-leaved, dry spell tolerant, evergreen trees (Figure 4), and an atmosphere comprising of long, chilly winters and short, cool summers (Figure 11). Biodiversity is low right now forest made up of an overstory of trees and a ground layer of herbs or greeneries. The overstory is a significant part of the boreal forest comprised of just a couple of animal categories. The low biodiversity is reflected by low net essential profitability of 200–600 g m-2 yr-1. Profitability changes with precipitation, the length of the ice-free period, and neighbourhood soil seepage. In overflowed regions, sphagnum marshes may create. The acidic tissue of sphagnum, and the anoxic, overwhelmed conditions, eases back deterioration, bringing about the creation of peat lowlands.

Boreal forest biome atmosphere outline

Figure 11: Boreal forest biome atmosphere outline

Boreal forests are described by needle-leaved, dry season tolerant, evergreen trees, and an atmosphere comprising of long, chilly winters and short, cool summers.

Biomass in tree trunks and seemingly perpetual evergreen leaves brings about supplements being put away in the plants. Low temperatures lead to slow disintegration and high litter amassing. Up to 60% of the biomass might be tied up in litter and humus. Soils are vigorously drained, and permafrost underlies a significant part of the dirt. Like this, trees have shallow root frameworks and depend on broad mycorrhizal relationships for supplement take-up.

Tundra Biome

At scopes past the boreal forest tree line lies a boggy territory (Figure 4) where developing seasons are short, and temperatures are underneath zero degrees Celsius for a significant part of the year (Figure 12). In light of these low temperatures and short developing seasons, net essential profitability is low in the tundra, between 100–200 g m-2 yr-1. Profitability shifts with snowfall profundity and nearby seepage. Rough fields and dry glades will have lower profitability than wet, low-lying regions and wet knolls.

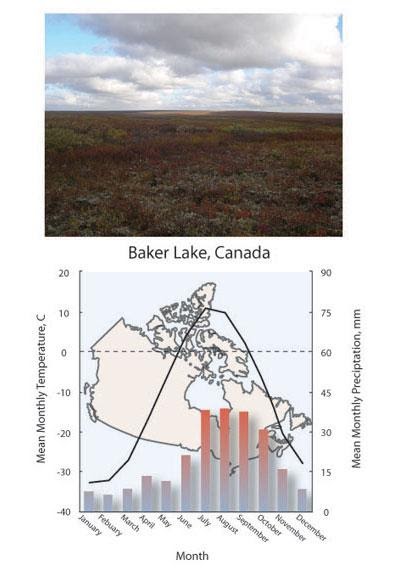

Tundra biome atmosphere chart

Figure 12: Tundra biome atmosphere chart

Exceptionally short developing seasons and temperatures that are underneath zero degrees Celsius for a significant part of the year describe tundras.

Biodiversity in the tundra is low and ruled by greeneries, lichens, and low-developing lasting bushes. The tundra biome contains just about 3% of the world’s greenery. Up to 60% of the verdure can be comprised of seemingly perpetual hemicryptophytes. Breezy conditions and low temperatures select for low developing bushes, frequently with firmly stuffed, adjusted overhangs with firmly separated leaves and branches. Wind and ice harm help structure this shape by pruning branches. The shade morphology decreases wind speeds and assimilates sun-powered radiation, bringing about covering temperatures on bright days more than 10° C above air temperature.

Soils are low in supplements because of moderate disintegration rates, and plants hold supplements in seemingly perpetual evergreen tissues. Nitrogen obsession by lichens with cyanobacterial segments is a significant wellspring of soil nitrogen. Creatures have broadened hibernation periods or move occasionally.

Read more about Tropical Rainforests

Frequently Asked Questions

What is a biome?

A biome is a large geographical area characterized by specific climatic conditions, ecosystems, and types of vegetation and wildlife.

How do temperature and precipitation patterns define different biomes?

Temperature and precipitation determine factors like plant types, animal adaptations, and overall ecosystem characteristics in each biome.

Give an example of a terrestrial biome and describe its characteristics.

The tropical rainforest biome is characterized by high rainfall, lush vegetation, and diverse animal species, with a continuous canopy of trees.

What is a marine biome, and how does it differ from freshwater biomes?

Marine biomes include oceans and seas, while freshwater biomes encompass lakes, rivers, and wetlands, each with distinct aquatic ecosystems and inhabitants.

How do human activities impact global biomes?

Deforestation, pollution, and habitat destruction by humans can disrupt natural biomes, leading to loss of biodiversity and ecological imbalances.

References

- Global Biomass. (n.d.). Retrieved from Geography: https://garsidej.wordpress.com/year-9/global-biomes/

- Major Biomes Of the world. (n.d.). Retrieved from WWF: https://wwf.panda.org/knowledge_hub/teacher_resources/webfieldtrips/major_biomes/

- Terrestrial Biomes. (n.d.). Retrieved from Knowledge Project: https://www.nature.com/scitable/knowledge/library/terrestrial-biomes-13236757/